by Dennis Giardina

The shade house contained Soroa’s main collection of native Cuban orchids. We followed him down a row with long benches of potted orchids on both sides of us, many of them hanging from pieces of wood and branches suspended from above. As we followed behind Dr. Perez, I spied one of our mutual native orchids in bloom, Prostechia cochleata, the clamshell orchid. I also noticed another flowering orchid that looked a lot like Encyclia tampensis, the butterfly orchid.

We have two species of native Encyclia orchids in Florida, the butterfly orchid which may be our most common epiphytic orchid, and Encyclia pygmaea, the dwarf Encyclia which is arguably our rarest. Cuba in contrast has sixteen species of Encyclia, including Encyclia pygmaea but it doesn’t have Encyclia tampensis, which is endemic only to Florida.

Biogeography is a pretty interesting thing; the way species arise, reproduce and spread or radiate. Orchids on islands like the ones in the Caribbean are especially illustrative of this. They all spread by seeds that are as fine as dust that get blown far and wide by the wind. Where those seeds land on friendly colonies of bacteria and fungi, they can germinate and grow. They adapt to different conditions and become isolated in their new environment until they speciate, or become genetically different enough from their founder population to be considered a distinct species. Our butterfly orchid surely arose from the seeds of a closely related Cuban species that were carried on the wind across the Straits of Florida to the Peninsula of Florida a long time ago.

Dr. Perez stopped at the corner of the row we were walking down but he didn’t even have to gesture or tell us anything; Mike and I saw them from a mile away. Something we only dreamed of seeing, there, hanging from pieces of wood, bearded with Spanish moss was Bulbophylum pachyrhachis! Rat-tail orchids, some in full bloom! It would be hard to exaggerate how ecstatic we both felt at that moment. Until then this little orchid had been an enigma to us, a legend. We knew it only from the accounts of where it was last observed and photographed in Fakahatchee around 1970.

Since then, multiple individuals have made repeated trips to that area and throughout the Fakahatchee’s Central Slough where the rarest native orchids grow on the limbs of gnarly old pop ash and pond apple trees below the cypress canopy, above pockets of deep flowing water, but no rat-tail orchids were ever found. Bulbophyllum pachyrhachis is apparently extinct in Fakahatchee, the only place it was ever known to occur in Florida.

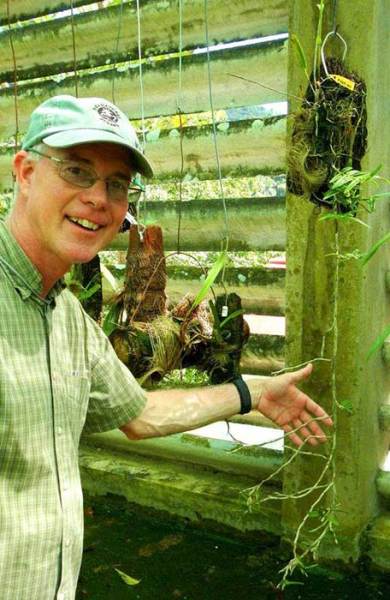

I pulled out my camera and I started to take pictures, and I probably would have taken hundreds of them if Dr. Perez didn’t signal to me for us to follow him down another aisle. He pointed to a cascade of stems and foliage, hanging down from a piece of wood suspended above a shallow cement basin filled with water. When I realized what it was, I couldn’t believe my eyes or our luck. There it was; Epidendrum acunae, the other one of Fakahatchee’s lost orchids! This one just might be more obscure than the rat-tail. It doesn’t even have a common name. It was named after Julian Acuna Gale, the Cuban botanist who described the species.

Like the rat-tail orchid, Epidendrum acuane has a huge range, throughout the Caribbean, Central and South America but they’re not really common anywhere. Throughout its range, Epidendrum acunae prefers to grow close to water, and I can imagine it once grew around some of the deep swamp lakes in Fakahatchee before the industrial logging and orchid collecting periods of the mid 20th century.

Before we left Soroa, Dr. Perez and I worked out some of the details of how we could collaborate to eventually transfer seeds of the two lost orchids from Soroa to Atlanta Botanical Garden. Hopefully this will happen this coming spring with Bulbophyllum pachyrhachis, a little later with Epidendrum acunae, which should begin to bloom in a few months. Mike and I have also started to lay the groundwork for hosting an international orchid restoration conference like the one we attended in Cuba, in May of 2015. Tim and Phil from the Royal Botanical Garden have offered to help us organize, and Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden has offered to host it.

The way it’s shaping up is that there will be three days of presentations over on the East Coast, and then we’ll move everyone over to Everglades City for three days of field trips in Fakahatchee, Big Cypress, and the 10,000 Islands. If we are able to start growing Bulbophyllum pachyrhachis from seed in Atlanta this year, we should have juvenile orchids large enough to experimentally outplant in Fakahatchee by then. The icing on the cake for me and Mike would be to have Dr. Perez and his daughter Yunelis there with us to be part of a pretty historic moment: the repatriation of the rat-tail orchid to Fakahatchee Strand Preserve State Park.

Dennis Giardina is the Everglades Region Biologist for the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission and was formerly the Park Manager of Fakahatchee Strand Preserve.