Lost and Found in Cuba, Part 7

by Dennis Giardina

Ask, and it shall be given you; seek, and ye shall find; knock, and it shall be opened unto you: For every one that asketh, receiveth; and he that seeketh, findeth; and to him that knocketh, it shall be opened.

Matthew 7:7-8

About twenty years ago I got the book The Native Orchids of Florida by Carlyle A. Luer. It was out of print, but I happened to find someone willing to sell me a copy of this big, almost coffee-table-sized hardcover. Originally published in 1972, it contains an impressive amount of good information and images of all the species found within the state. It has become one of the most useful reference books I have ever owned. When I first got it, I focused on learning the epiphytic orchids of the Fakahatchee Strand, especially the rarest ones. Two species stood out to me: the rat-tail orchid, Bulbophyllum pachyrachis, and Epidendrum acunae, because they were documented and photographed in Fakahatchee by Dr. Luer during the 1960s. Apparently not long thereafter, they became extinct. I read the descriptions of these “lost” orchids and studied the photos over and over.

I started to explore the deep sloughs of the Fakahatchee Strand, looking for rare orchids, wondering about the two extirpated species and if they could still be out there somewhere. I got to know and then work with Mike Owen. About ten years ago Mike and I started a conversation about finding the lost orchids, one we’re still having. We have repeatedly explored the areas where they were last seen in Fakahatchee, and we’ve searched for them in other remote places. This includes western Cuba, which is where I found myself on a lovely autumn morning in the Zapata Swamp Biosphere Reserve, sitting in the crotch of a tree that was covered by a hundred or more rat-tail orchids with dozens and dozens of flower spikes in full bloom.

Yes, there were several seed capsules as well. Whatever insect pollinates this species had already done its thing to some of the earliest flowers at the top of a few of the long, fleshy peduncles. Aside from the mystique of being one of the lost orchids, the rat-tail orchid, Bulbophyllum pachyrachis, has to have the most bizarre flower of any of our native orchids. The peduncle or flower spike usually hangs from the plant like a skinny spear of asparagus, upon which emerge dozens of weird little flowers that look like lobster claw meat. They start at the base, descending along the length of it as the inflorescence matures.

Close-up of Bulbophyllum pachyrachis fruit.

The genus Bulbophyllum is not very well represented in the Western Hemisphere, but on the other side of the world, it is extremely well represented. In fact, it may be the most speciose genus in the orchid family, with over 2,000 known species. The center of evolution and diversity of the genus is in the montane rainforests of Papua New Guinea, where more than 600 species have been documented. An internet search for images of Bulbophyllum orchids will reveal some of the wildest looking flowers of any group of plants on the planet. Whether the inflorescence of the species B. pachyrachis looks like a rat’s tail or not, I’ll leave to the eye of the beholder, but cascading down from this impressive colony were many inflorescences, some over a foot long.

I was thrilled when I first saw this species in bloom at Soroa Botanical Garden in October, 2012 (see Lost & Found in Cuba, Part 2). Up until then, I only knew it from the pictures in Dr. Luer’s book. I was astounded by this exuberant, wild colony of rat-tail orchids, and it was only the first of four populations that we visited and examined that afternoon.

The next day Dr. Rolando Perez, Director of Science at Soroa Botanical Garden, and I returned to Soroa. The following morning I set out at day break with two guys from the Botanical Garden to explore the Rio Tacotaco in the Guaniguanico Mountains. Somewhere up this river, a population of Epidendrum acunae was documented, and to find it was our mission. Rolando dropped us off at a bridge at the base of the mountain, and we hiked up the river, crossing it a bunch of times rock to rock. It was a beautiful, cool morning due to the passage of a cold front that we felt all the way down in Zapata the day before.

Lesser Cuban Racer (Caraiba andreae).

The sunrise over the karst hills was spectacular, and the rising temperature brought out some reptiles to bask along the open trail. The first one we came across was a Cuban racer, Cubophis cantherigerus, that unfortunately had its head removed by someone with a machete not long before we showed up. A bit further up the trail we came upon another snake, a lesser Cuban racer, Caraiba andreae, stretched out in a patch of morning sunlight. It was shiny black above, creamy white below, and very tolerant of my camera.

As we worked our way up the mountain, the forest surrounding the river became taller and its canopy wider. We started to see more bromeliads and other epiphytes, and at some point our path led us through a grove of planted coffee, then through the front yard of the man who cultivated it. On his roof, coffee beans drying in the sun. In the back yard, coffee beans fermenting in a wooden bin. And on his little stove, hand roasted, hot brewed coffee that he apologetically served to us in little aluminum cups. After a brief visit we headed back down to the river with a caffeine-inspired bounce in our step, and I asked the guys to guess when the last time a gringo had set foot there. They looked at each other, shrugged and one said, “Maybe never.”

Back on the river we continued our search for Epidendrum acunae. The guys were told more or less where to look for it, but neither of them had seen it before. We were told that it was considerably large, growing fairly high up in a tree, but that was all. We came to a place where the river narrowed into a shallow, fast-moving riffle that cascaded downstream. The banks of the river were steep, and in the middle of the river was an enormous, vegetation-covered boulder that diverted the flowing water around it. It apparently also blocked the downdraft of air from the river above, creating a microclimate with a higher relative humidity than anywhere else around it.

On the downstream side of the boulder was a stand of Royal Palm trees, growing in an accretion of rocks and sediment. When I scanned the moss and lichen covered trunks of the Royal Palms I noticed a big bare patch on one of them about twenty-five feet up. Below it I noticed three pendent but upturned orchids studded with long, narrow leaves. When I focused in on them with my binoculars, I realized that I was looking at Epidendrum acunae! Wow!

Epidendrum acunae babies below.

When I looked around the bases of the palms and on some of the other tree trunks next to them, I found a bunch of juveniles, some barely an inch long. We hypothesized that a mature plant once clung to the Royal Palm at the bare patch, then it became heavier than the roots could handle. Eventually rain and wind peeled it off and knocked it down into the river. I expect that a reproductive population of Epidendrum acunae will eventually reestablish there from these young plants, but it will be years before any of them could be expected to flower and fruit. We searched the river and its banks around this site for several more hours, but we did not find any more specimens outside of this sheltered pocket. One notable thing though – growing along this little stretch of the Rio Tacotaco, within a couple of hundred feet of this cluster of Epidendrum acunae, were the other three lost orchids: Brassia caudata, Macradenia lutescens and Bulbophyllum pachyrachis.

We finally had to stop our search and descend the mountain to meet Rolando, who brought with him a bottle of rum that the four of us shared while we recounted the day’s adventure. On our drive back to Soroa, I asked Rolando to pull over so I could take a picture of the mountain range illuminated by the setting sun. I stood there for a moment and reflected upon the events of this trip. I offered up my overwhelming gratitude to the universe and then I got back into the car.

To be continued…

Dennis Giardina is the Everglades Region Biologist for the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission and was formerly the Park Manager of Fakahatchee Strand Preserve.

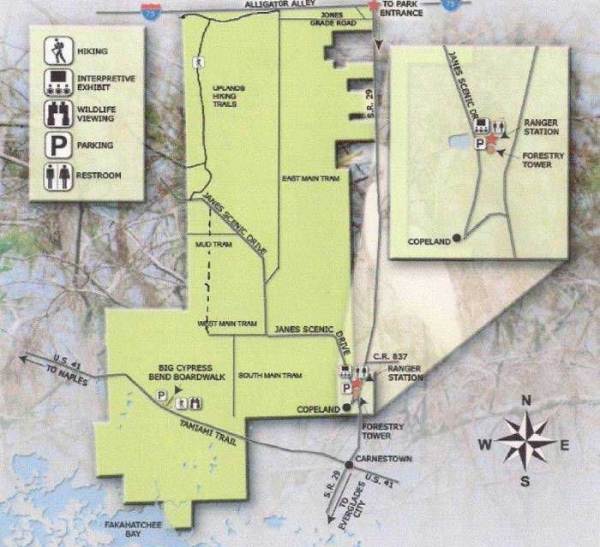

Friends of Fakahatchee Vice President Patrick Higgins checks out the silt fences on the north side of the Tamiami Trail at the Big Cypress Bend Boardwalk. They were installed by the state to prepare for the installation of a deceleration lane that will eventually lead to a new paved parking area. The FOF, working with the Florida Park Service, have developed a multi-year Boardwalk Expansion Project to significantly upgrade the site.

Friends of Fakahatchee Vice President Patrick Higgins checks out the silt fences on the north side of the Tamiami Trail at the Big Cypress Bend Boardwalk. They were installed by the state to prepare for the installation of a deceleration lane that will eventually lead to a new paved parking area. The FOF, working with the Florida Park Service, have developed a multi-year Boardwalk Expansion Project to significantly upgrade the site.