by Patrick Higgins

Photo by Rose Flynn

For a change of scene I decided to visit a cypress dome instead of a prairie hammock. The mid-December day I choose coincided with the passage of a rapidly moving cold-front, so I set off under a grey sky. I had noticed a classic dome on Copeland Prairie on a previous excursion and thought it would be fun to investigate, as domes are really the opposites of tree islands, as I shall later explain. My target was located 1• miles up the track running north from the first bend of Jane’s Scenic Drive.

I had expected the Prairie to be essentially dry like Lee-Cypress across the road, so was lazily sporting calf-high Wellington boots appropriate for muddy English country walks, but which would fill with water if overtopped. As it turned out several inches of water remained, perhaps because of JSD’s damming effect. I found that I had to teeter-totter along the track’s central ridge to avoid sections where the ruts were perilously deep – something I wouldn’t have thought twice about if I was wearing my regular ‘wet’ boots. But this gave me the opportunity to observe the little mosquito fish that had been concentrated in them and only weeks before were spread all across the Prairie.

Photo by Patrick Higgins

Dull light isn’t the best to appreciate the Florida landscape, but to either side, bare hat-rack cypress stood like lonely sentinels. These dwarfs, standing only 10-15 feet high, are stunted pond cypress that eke out a meagre existence on slivers of soil over the prairie’s bedrock and may actually be over 150 years old, deserving our respect. There’s debate whether pond cypress are a separate species from bald cypress (Taxodium distichum) or merely a variety of the same species (var. nutans) but opinion seems to be leaning towards the latter. Whatever the taxonomy, pond cypress do have special adaptations to the harsher niches they occupy, including thicker bark to increase fire resistance and needles closely appressed to their upturned branchlets to aid in water retention, versus the droopy feathery branchlets of bald cypress.

All around me the almost fluorescent, blue, bobbing heads of Glades Lobelia visually popped against the dry grass along with the intense white of String Lilies in their prime. There were still the occasional Grassy Arrowhead in bloom, but these had long peaked and were looking forlorn. Crushed Water Hyssops underfoot released a minty-lemon fragrance and attracted White Peacock butterflies. Frosty-colored Liatris seed heads released tufts of white as I brushed by, and the odd apple snail shell caught my attention. With the sound of the wind as a companion, I had a delightful hour’s hike to the dome. A line of Slash Pines, perhaps only inches higher in elevation gradually closed in from the west at my destination leaving only a narrow gap for the track to continue onwards.

As if on cue a ray of sunshine pierced the clouds transforming the grey leafless dome momentarily to gold. With the Sun appeared several Halloween Pennant dragonflies and a Scarlet Skimmer. I stopped to take a photograph and despite the shallow depth of the mud, my boots began to stick, pulling out with a distinct pop as I left the track to approach the dome. My cypress stand was some 80 yards in diameter. Classically lower trees encircled it and each succeeding concentric ring rose slightly higher creating a perfect dome shape with the tallest trees towards the center perhaps as high 70 feet and certainly besting the tallest pines nearby.

To the uninitiated cypress domes are counter intuitive. They appear from a distance almost as little hillocks but are in fact water-filled depressions, at least in the wet season, which brings us back to opposites and prairie hammocks. Those tree islands typically develop on limestone outcrops that raise them slightly above the surrounding terrain. Cypress domes, however, form in slight depressions created when weaker areas of limestone bedrock subside or dissolve from the action of the acidic by-products of rotting plant material. One might think the taller trees in the middle represent greater age, but the difference in height may be down to increased growth vigor instead.

Photo by Rose Flynn

Imagine a newly formed depression on the prairie. The initial trees that colonize the beginnings of that ephemeral pond will have no better soil conditions than our hat-rack cypress. So an outer ring of stunted trees develops. Over time they drop their needles into the pond creating slightly better soil conditions for the next ring of trees which grow slightly taller, and so on and so on. Each successive ring also has a slightly longer hydroperiod because they are further into the bowl. So the tallest trees may not necessarily be the oldest trees, rather they have just experienced the best growing conditions. And to confound the model, were we able to count the tree rings of outer individuals, they might not be older because the outer trees also experience the highest mortality due to a shorter hydroperiod and greater susceptibility to fire.

Cypress trees, like all aquatic organisms, face certain challenges from being periodically inundated. Water is an excellent solvent, able to readily transport most chemicals required for life, but it’s also about 10,000 times more viscous than air, meaning that life supporting gases, primarily oxygen and carbon dioxide move very slowly in their dissolved state, requiring special adaptations. Water lilies for example have hollow stalks so that oxygen can be channelled to roots buried in anaerobic muck. On the outer fringes and into the dome’s interior I encountered cypress knees; those knobby conical structures that have proved such a mystery to scientists.

All sorts of sophisticated experiments have been conducted over the past 80 years, even hermetically sealing them in transparent cases with hoses connected to all sorts of instruments, but the results are inconclusive or contradictory. However, most likely they are involved in some sort of gas exchange as they typically grow to an average height just above the local site’s mean high water level, and they also provide some sort of anchoring mechanism as they typically appear where the root system takes a distinct downward turn, perhaps here in South Florida exploiting a small solution hole. We also know they store starch.

Although the dome was dominated by cypress there was a struggling understorey kept in check by the cypress canopy’s shade. It comprised pond apple, Dahoon holly, pop ash, a few Carolina willow and some cabbage palms near the outside; all species that create a succession canopy in swamps if there is a perturbance like logging or fire. This one sheltered some sparse sawgrass too.

The cypress trunks had characteristic buttressed bases. These swellings help them absorb oxygen and provide stability in high winds. I could detect the normal high water level from the line where the patches of lichens ended. The closely spaced trunks serve to dampen air movement and trap moisture under the canopy, so that higher up, the cypress branches were festooned with bromeliads.

Cypress cones. Photo by Rose Flynn

Waxy cones and pendulous catkins hung on many of the cypress and the typically clear water below was instead dusted with their pollen. Each cone typically contains 16 seeds that � look a bit like dried-up petals the size of a finger nail. Squirrels often messily tear apart ripe cones and in the process drop seeds. In the not so distant past noisy flocks of now extinct Carolina Parakeets would have also performed this service. The seeds then need a complex sequence of conditions to successfully germinate. Ideally they will fall into water where they can soak for several months to soften their tough outer husks, but they can’t germinate there and must ultimately settle on exposed, but moist soil. This is why cypress trees need alternating wet and dry.

The seedling then must quickly thrust upwards to avoid being submerged when the rainy season returns or they’ll drown. Once mature however, they can survive both periodic flooding and drought. Because of this, if there’s permanent water in the center of the dome, there will be what looks like a donut hole from the air, devoid of cypress.

My dome was true to form and sure enough as I sloshed inward I encountered a small flag pond open to the sky. The alligator flag indicated even deeper water. Had I been a truly dedicated scientist I would have waded into the center to measure the depth, but in the dry season these frequently become gator holes, and as I was alone and had the excuse of inappropriate boots, I opted just to admire the pond then head home. My hike back was much quicker as I decided to bypass the rutted track altogether and found it much faster striding over the firm prairie in just a few inches of water. It helps to have long legs though!

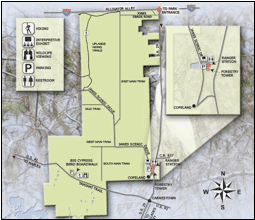

Nestled in the northeastern corner of the Fakahatchee and within the Preserve is a group of picturesque lakes formed from gravel pits that were dug during the building of Highway 75 known as Alligator Alley. The lakes are linked by berms which are rough but drivable if you have adequate clearance, or otherwise mountain bike or hike.

Nestled in the northeastern corner of the Fakahatchee and within the Preserve is a group of picturesque lakes formed from gravel pits that were dug during the building of Highway 75 known as Alligator Alley. The lakes are linked by berms which are rough but drivable if you have adequate clearance, or otherwise mountain bike or hike. by Patrick Higgins

by Patrick Higgins The entrance to East Main trail Gate #12 is approx. 6 miles up the unpaved Janes Scenic Drive where you will see ample parking, at this point Janes Scenic is gated and visitors can continue to hike or cycle Janes Scenic drive. A kiosk with information is located at the entrance of the East Main trail gate #12 . Over your 6 mile drive you will have passed through scenic wet prairies interspersed with hardwood tree hammocks, before entering a dense cypress forest containing a large variety of trees, ferns and bromeliads which thrive in the humid sub-tropical climate which exists here.

The entrance to East Main trail Gate #12 is approx. 6 miles up the unpaved Janes Scenic Drive where you will see ample parking, at this point Janes Scenic is gated and visitors can continue to hike or cycle Janes Scenic drive. A kiosk with information is located at the entrance of the East Main trail gate #12 . Over your 6 mile drive you will have passed through scenic wet prairies interspersed with hardwood tree hammocks, before entering a dense cypress forest containing a large variety of trees, ferns and bromeliads which thrive in the humid sub-tropical climate which exists here.

About 1 ¾ miles up Jane’s Scenic Drive just after the first bend there is a distinct ecotone where the prairie on either side abruptly transitions to forest. You’ve entered Fakahatchee’s strand; the world’s largest subtropical strand swamp and a geological feature unique to southwest Florida that provides habitat for many threatened or endangered species. Technically a strand is simply a shallow, water-filled channel in which trees are growing. But it’s more than that. The Strand’s canopy moderates extremes, creating a microclimate that retains humidity, making it just a little bit cooler in the summer and a little bit warmer in the winter. This in turn allows a rich community of native bromeliads, ferns and orchids to flourish; it literally drips with life.

About 1 ¾ miles up Jane’s Scenic Drive just after the first bend there is a distinct ecotone where the prairie on either side abruptly transitions to forest. You’ve entered Fakahatchee’s strand; the world’s largest subtropical strand swamp and a geological feature unique to southwest Florida that provides habitat for many threatened or endangered species. Technically a strand is simply a shallow, water-filled channel in which trees are growing. But it’s more than that. The Strand’s canopy moderates extremes, creating a microclimate that retains humidity, making it just a little bit cooler in the summer and a little bit warmer in the winter. This in turn allows a rich community of native bromeliads, ferns and orchids to flourish; it literally drips with life.