Hiking and Biking the Fakahatchee

by Anthony (Tony) Marx

Note: this article was written by the author in 2015 and updated by the Friends of Fakahatchee in 2022. For current trail conditions call the Fakahatchee park office at 239-961-1925.

In my December 2014 Ghost Writer article I described off road ‘mountain’ biking in the Fakahatchee State Park and this will serve to acquaint visitors with what they can expect to find either hiking or biking the trails kept open for public use.

There were once 200 miles of rail tracks laid within what now comprises the Fakahatchee Strand Preserve State Park which gradually fell into disuse by the late 1950’s when logging ended and the property was sold to developers. The rails and ties were removed although some of the latter can still be seen laying where they were discarded alongside Janes Scenic Drive (JSD). Even the Drive itself was a railroad to which were connected the main arteries and served the interior shorter branch tracks feeding into it from north and south.

Ballard Camp, viewed from the north side, is on East Main.

The Developers scammed people into buying small building lots, as happened in the adjoining Picayune State Forest although not on such a large scale, and some remain hidden in the forest today, referred to as ‘in holdings’. Permanent occupation is not feasible simply because building is not permitted and an in-holder’s camp may simply consist of a bare patch of land partially flooded in summer or an old crumbling shack left over from the 1970’s when the land was acquired by the State of Florida and designated a Park and Preserve – the largest in Florida. Believe it or not, there are still almost 1000 such lots scattered throughout the Park with most hidden away in the depths of the swamp.

The 200 miles of trails have almost all disappeared, reclaimed by Mother Nature. Park Staff assisted by volunteers with the Friends of the Fakahatchee manage to keep open what remains. Mentioned below are trails that can be cycled or hiked.

Janes Scenic Drive (JSD)

Janes Scenic Drive (JSD)

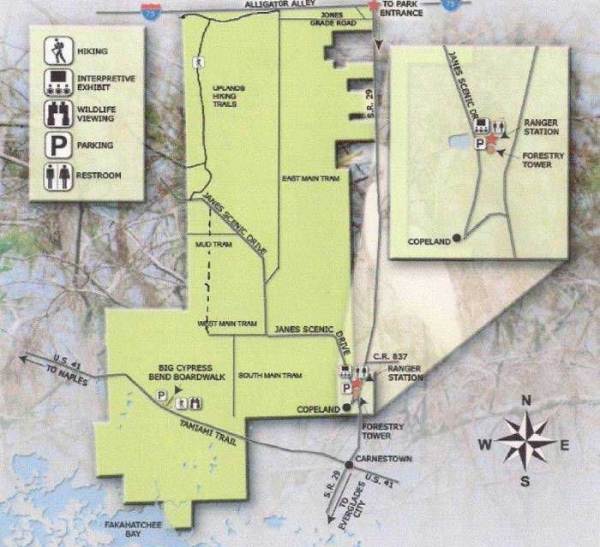

This main road bisecting the Park is accessed only from State Road 29 at Copeland. JSD paving ends just past the Park Ranger Station. JSD continues N.W. for 12 miles however it is gated at the 6 mile point where visitors will find ample parking and can continue on JSD to hike or cycle. JSD is a narrow, bumpy dirt road running through the heart of the Swamp forest, with several places where you can park to hike or bike. Of course, lock your vehicles and stow valuables out of sight.

The following trails are all double track with grass between. They meander through tall pristine forest and luxurious understory festooned with ferns and bromeliads. Wildlife encounters of all kinds happen on a regular basis, so keep your camera handy.

West Main Hiking Trail Gate #7

The gated entrance to the trail is approx. three miles from the start of JSD, a kiosk with information is at the entrance of the trail. A double track ends at a small open prairie 3 miles from the trail head. At this point you have two options. The first option is to backtrack to the trail head after a mildly strenuous ride at about 7 mph. The second, more strenuous option continues north across the grassy prairie and connects with Mud Tram trail (see dotted line on the map). Side trails make a compass or GPS mandatory, as the trail is not marked.

East Main Hiking Trail Gate # 12

This is the main hiking trail with ample parking, located on the right of JSD approx. 6-1/2 miles from the start. The first 2-1/2 miles are easy double track and bring you to an in-holding known as ‘Ballard Camp.’ This privately-owned corrugated iron cabin was once a logging supervisor’s cabin and is kept in good shape by its owners. They kindly allow visitors to rest on the front porch, but please respect their privacy if they are present – accompanied by their vehicle parked nearby. They maintain a jetty running from the back of the cabin to a lake which is always busy with alligators large and small.

Bear right past the cabin and the trail continues for another half mile to eventually become impassible. The trees here are heavily festooned with bromeliads.

Tony Marx is a Florida Master Naturalist and former FOF Board Member.

There is some debate about what constitutes a Snag, Is it a dead tree? Is it on the ground? Is it in the water? Is it a loose thread? The Urban Dictionary defines snags as a “sensitive new age guy.” So, there are many definitions … For our purposes, a Snag is a standing dead or dying tree.

There is some debate about what constitutes a Snag, Is it a dead tree? Is it on the ground? Is it in the water? Is it a loose thread? The Urban Dictionary defines snags as a “sensitive new age guy.” So, there are many definitions … For our purposes, a Snag is a standing dead or dying tree.