Beneath the Prairie

By Patrick Higgins

I happened to step out on the south end of Lee-Cypress Prairie on the very day in mid-October when the last of the water receded. That event was so fresh the black mud was still glistening. As I stood still to take in the scene I could hear water seeping back into my footprints. The grassy arrowhead, whose white billowing flowers had dominated the prairie only weeks before had now mostly gone to seed.

I happened to step out on the south end of Lee-Cypress Prairie on the very day in mid-October when the last of the water receded. That event was so fresh the black mud was still glistening. As I stood still to take in the scene I could hear water seeping back into my footprints. The grassy arrowhead, whose white billowing flowers had dominated the prairie only weeks before had now mostly gone to seed.

This year’s rain had come early and heavily, and as the whole Prairie tilts ever so slightly to the southwest, water had stood here long and deep enough that most of the clumps of bunch grass had rotted away. This left wide spaces between each arrowhead plant. On the surface between them was a patchwork of overlapping prints from half a dozen species of wading birds that had feasted here only days before on their concentrated prey of amphibians, small fish and crustaceans. They had now moved on.

This year’s rain had come early and heavily, and as the whole Prairie tilts ever so slightly to the southwest, water had stood here long and deep enough that most of the clumps of bunch grass had rotted away. This left wide spaces between each arrowhead plant. On the surface between them was a patchwork of overlapping prints from half a dozen species of wading birds that had feasted here only days before on their concentrated prey of amphibians, small fish and crustaceans. They had now moved on.

But something else was happening. All around me the surviving crayfish were busy excavating their burrows down to the water table where they would spend most of the dry season. Their chimneys looked like piles of miniature black meatballs and their earthworks contrasted starkly in patches where the dun-colored periphyton had already dried.

At 3 to 5 inches, crayfish are the Park’s largest invertebrates. There are something like 350 species in North America. Some are obligate burrowers and others not, and many of them are such habitat specialists that they may occupy only one particular river basin system. We have more than 50 species here in Florida, even some cave dwelling troglodytes, and two that make the Fakahatchee their home. These are the similar looking Everglades Crayfish (Procambarus alleni) that we find on the wet prairies and the Slough Crayfish (P. fallax) who are less adapted to seasonal drying and favor more permanent water like their namesake sloughs.

Crayfish are non-selective omnivores. They will eat almost anything organic they can catch or scavenge and chop up small enough to put in their mouths, including algae, plant material, fish eggs, worms and insects. But they’re also cannibals too, usually directed from larger to smaller and particularly molting individuals. Like all arthropods they have a rigid exoskeleton and need to periodically molt to grow, and it is at this stage that they are most vulnerable. Maybe because of this females exhibit some parental care.

Most crustaceans release their eggs into the water and do not care for them. Crayfish females carry their eggs on their swimmerets to protect them from predators and here they hatch as perfect miniatures and go through three molts before releasing and taking up free-living lives, thus increasing their survival rate.

They reach sexual maturity in about two months and probably live up to three years although chances of surviving that long are pretty slim. There are sharp beaks everywhere. Females in their burrows are egg laden at the end of the dry season and young crayfish are very quickly able to repopulate newly flooded prairies. This makes them critical prey for wading birds in the lag before fish species appear in any quantity.

Crayfish are a vital component of Fakahatchee’s food web by dint of both their sheer numbers and because virtually anything that can catch a crayfish will eat it. There are at least 40 species of vertebrates that feed on them: from fish to pig frogs, water snakes, young alligators, raccoons and wading birds. They are a particular favorite of ibis who use their long curved bills to probe for them. On my visit the exposed mud was still pitted with holes from their foraging.

The numbers of crayfish tend to increase with the plant community’s complexity as this provides both shelter from predators and increased food resources. True to form, where I first stepped on to the denuded beginning of the Prairie, I was observing about 2 – 3 burrows per square meter, but by a quarter of a mile in, where there was more vegetation, up to eight, and remember this was after the feasting of the dry- down when the population is at its lowest.

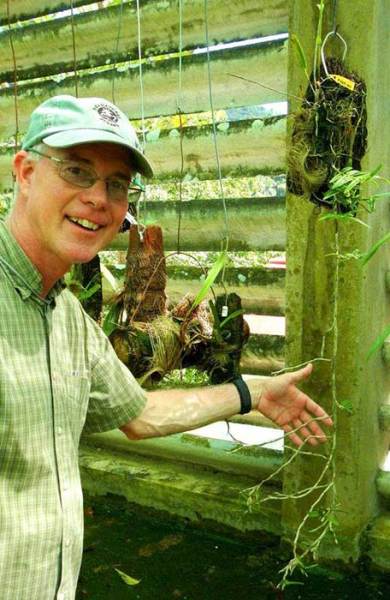

crawdad image

But their role as a food source is only part of their importance. In wet prairies they may be considered a keystone species with a role analogous to that of the gopher tortoise in the pine flatwoods, but on a miniature scale. Crayfish burrows serve as refuges for many other small aquatic organisms that retreat to them as the prairie dries and then quickly repopulate it when water returns. Also by heaping up piles of earth they are creating perfect habit for seeds to grow where fire has not exposed the soil. Whatever name you call them: crayfish, crawfish, crawdaddies or mudbugs, crayfish are a vital part of the Fakahatchee’s ecosystem.